How Miguel and I Met.

Miguel and I have known each other for over 13 years. We first met while trying out for the Agua Fria High School soccer team. It was through our passion for soccer that we became close friends. On our off seasons we would train together, with time we went on to play for the same club team, after high school we played college together at Gateway. Together, we compete and manage an indoor team on Monday’s. Miguel continues to play almost every day of the week. I chose to interview Miguel and tell his story because I was fortunate enough to learn through his challenges how being an immigrant has hindered his ability to freely experience many of the privileges that natural born citizens take for granted. Our interviews were conducted in Miguel’s backyard. The questions I posed were directed towards discussing many of the events that led Miguel to migrate from Mexicali, Baja California to Avondale, AZ, leading to where that places Miguel in the present, as well as in the near future. The narrative below is written by me, Jonnathan Flores, in the first perspective as if I were Miguel.

A Dreamer Named Miguel.

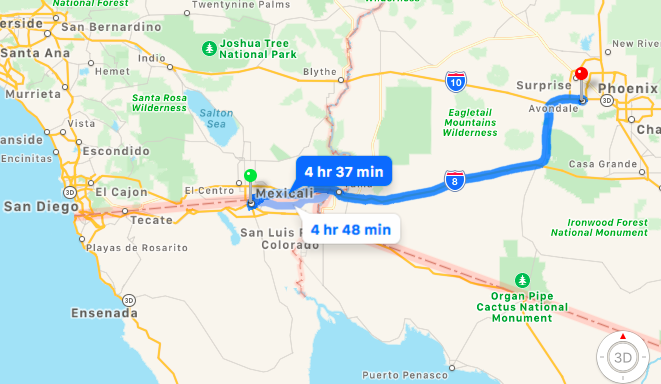

The image on the left shows the distance that Miguel traveled via truck to get to Avondale, AZ.

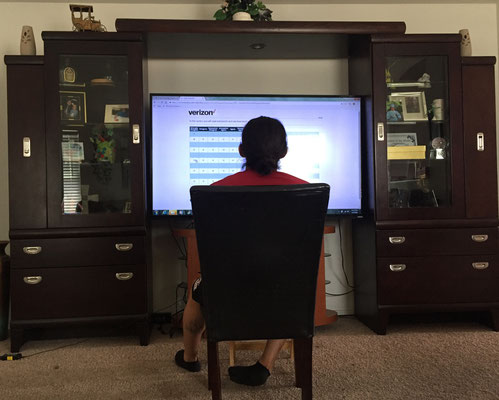

Thanks to DACA, Miguel's work permit grants him the opportunity to apply for jobs in the comfort of his own home.

I was born in Mexicali, Baja California. When people ask me what it was like to grow up in Mexico, I have a hard time remembering what that was like. In many ways, the neighborhood and home I left wasn’t much different than the ones I immigrated to. What I can say is that in Mexico, although we may not have had A/C, there was always something to do outside. Kids could either be seen playing tag, hide and seek, riding their bikes, or playing soccer in the street, and when cars would drive by, we would scatter to get out of the way. On the contrary, when I do tell others that I was born in Mexico, some don’t always believe me. If I were to say why, it would probably have to do with the way I sound, and the way I look. Although I was born in Mexico, I’ve lived in Avondale, AZ since the age of seven. As a result, I’ve assimilated to American life in Arizona. However, my time here as an immigrant, or as a Dreamer, has been everything that American life isn’t. During my time here, I’ve been subject to overcome obstacles that differ in comparison to those with citizenship. In this personal narrative, we will revisit the motives that drove my grandparents to emigrate me out of Mexico, and what my experiences were like growing up in the state of Arizona where immigrant sentiment is heavily contested.

When I was six years old my mother left my twelve-year-old brother and I to go live in the United States. I was told that she was staying in Oakland, California. Thankfully, my aunt took both my brother and I, providing us with a place to shower, eat and sleep. Not much later my Nana came down from Arizona to help my aunt take care of us. One year later, early in the morning, on April 15th of 2000, my nana packed the majority of my things in her Mazda truck before taking off. Unbeknown to me, that would be the last day I’d see Mexico. It wasn’t until we were approaching the nearest checkpoint to the U.S. border that I was told that we were going to be crossing the border into the United States. I laid underneath the backseat of my nana’s Mazda truck, hidden under piles of clothes, blankets, suitcases, and anything that would help to conceal me. We were at the border and slowing down, I remember sweating from how hot it was to be laying underneath all sorts of clothes and blankets, on top of that I was scared. I was unsure of why I had to be hidden. I didn’t know what was going to happen if we caught, my mind raced with uncertainty. We finally came to a stop, a border agent walked up to my nana’s window, she rolled down her window and said the words, “I’m an American citizen”. With that we were granted permission to cross into the United States. I remained in the backseat, still hidden for the entirety of the ride. We finally arrived at an AM/PM in Avondale, AZ. My growling stomach matched my hunger, and my curiosity. That was the first time I had tasted or seen a burger, and everything about it just made sense. Later in the day, I found out that my mom moved down to Avondale, AZ and asked my nana to bring my brother and I. However, my older brother didn’t come with us, he was still in Mexico. Fifteen days later, on April 30th, my nana would drive to Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico to pick up my older brother and bring him back the same way that I came, he was thirteen. Looking back, I sometimes wonder why I was brought here. Being poor here was better than being poor back home, plus we were together now.

By the time high school came around, a few things had changed. My Spanish accent was gone, and I felt confident when speaking English out loud. At fourteen I began working whenever my brothers friend needed some help cleaning people’s yards, during the summer we would sometimes go out to clean pools, and at times I would even help him move furniture into people’s homes. Throughout high school, these were the types of jobs that were available to me. In 2010, Arizona passed SB 1070 which requires police to determine the immigration status of someone arrested or detained when there is “reasonable suspicion” they are not in the U.S. legally”. I was constantly reminded that this was real because of how often it was publicized on the news. The University of Arizona investigated some of the impacts caused by SB1070 on Arizona’s youth, and discovered two distinguishable patterns which caused an increase in social disruption and institutional mistrust. Social disruption occurred at school or at work effecting children and businesses. Fear from SB 1070 led many immigrants to leave Arizona, oftentimes leaving their children behind to finish school (Southwest Institute for Research on Women, 2011) Institutional mistrust extended not only to law enforcement, but a mistrust against school systems, resulting in a decline in both parent involvement and a decline in the number of students attending schools. SB 1070 was passed during my senior year in high school. I really felt the dangers of SB 1070 after a soccer game, my friend drove me home when we got pulled over on the street that I lived for “making a wide turn”, when my friend and I both knew he made an appropriate turn. My friend driving was well aware about SB 1070, and he also knew that I was undocumented, which meant that if discovered, I would face deportation, he would also be subject to facing punishment. He told me to be quiet and let him do all the talking. Even when the police officer approached my door and asked me to roll down the window I let my friend do all the talking. When the officer asked for my I.D., all I had to show was my high school I.D. Before high school, I knew that I was different, but during high school it became aware that I was also disadvantaged. I couldn’t drive because I wasn’t allowed to have a state I.D., I couldn’t have a normal job, college wasn’t possible, and now I also didn’t feel safe outside or being in a vehicle with a friend. After graduation I found some work at a lawn mowing company where I would run the store from 8:00 a.m. to 3 p.m. In a week, I saw around $200.00, which breaks down to $5.00 an hour. However, that job didn’t last very long, in a few months that same lawn mowing company closed down, which meant that I had to find work somewhere else.

On June 2012, the Obama Administration developed the DACA program to help protect minors who were brought to this country at no fault of their own (NPR, 2017). My brother and I are 2 of 800,000 immigrants to receive protection from the program. Through DACA I was able to acquire a driver’s license, I was given a work permit that I used to begin working at Wal-Mart, and if I decide to, I’m able to enroll into college and further my education. In order to be approved for DACA, applicants must be younger than 31 years old when the program began, applicants must prove they’ve been living in the United States since June 15, 2007, and that they had arrived in the U.S. before the age of 16. Becoming a Dreamer gave me more confidence, and for the first time ever, it felt like progress was finally being made to better my situation and the many others who also identify themselves as Dreamers. I’ve renewed twice before, and I’m looking to renew for my last time. However, since the 2016 Presidential Election of Donald Trump, anti-immigration sentiment has been expressed throughout his campaign, and manifested into action on Tuesday September 5th 2017. On this day, Trump not only ended DACA, but he also placed the burden and responsibility on congress to try and save DACA in six months. Today, unfortunately I’m left uncertain of what my future holds, especially because I’ve spent time, effort, money, and even risked deportation by trusting the very same government that has now turned its back on me and 800,000 others alike.